Mayor Phil Hardberger doesn't waste words, but he can become downright loquacious when describing the 300 acres of oak savannah known as Phil Hardberger Park. Mayor Hardberger describes the park as "an oasis."

"For those of you who haven't seen the virgin land, it is truly a humbling and awe-inspiring experience," he confessed in his 2007 State of the City address. "It may even move you to hug a tree, though you won't be able to get your arms around many of them."

Their girth and age even provoked this nostalgic reverie: "To walk among those trees - many older than the heroes of the Alamo - is to know our history," he enthused. "It is a breathtaking expanse of urban wilderness."

Although the tract is neither pristine nor wilderness because the North Side site was a working farm for generations, the mayor's more important insight is spot on: Phil Hardberger Park offers us an unparalleled chance, even if only momentarily, to step outside of our decades-long mad rush to pave over every square inch, which has flattened San Antonio's contours and homogenized its vistas, crowding each with malls, freeways and subdivisions. Against this jarring backdrop, Phil Hardberger Park will be "an oasis," Hardberger affirmed, "and it is now ours to keep.

How we will keep its quiet beauty is a vital concern, because the city parks inventory contains only 14.5 acres per 1,000 residents, two acres less than the national average.

The gap used to be wider. Forty years ago, we had less than half the national average, and while we have made up ground, that may not remain true. In the 2000 census, for instance, San Antonio experienced its first increase in density since 1950, a pattern that will continue if our regional population hits the 2.5 million predicted for 2040, pressuring our already stressed parks.

This head-shaking projection is why it matters how Phil Hardberger Park (and subsequent open space) is designed.

Believing that this bucolic parcel could become a signature landscape, with an impact akin to that 19th century gem, Brackenridge Park, the city launched an international competition to entice renowned landscape architects to bring their perspectives to bear on Phil Hardberger Park.

They did. I was a member of the jury evaluating their proposals and was blown away by the diversity in design and detail, from the clever treatments of terrain and topography to the artful use of native flora and local culture. They understood us in ways we often miss about ourselves and the places we inhabit.

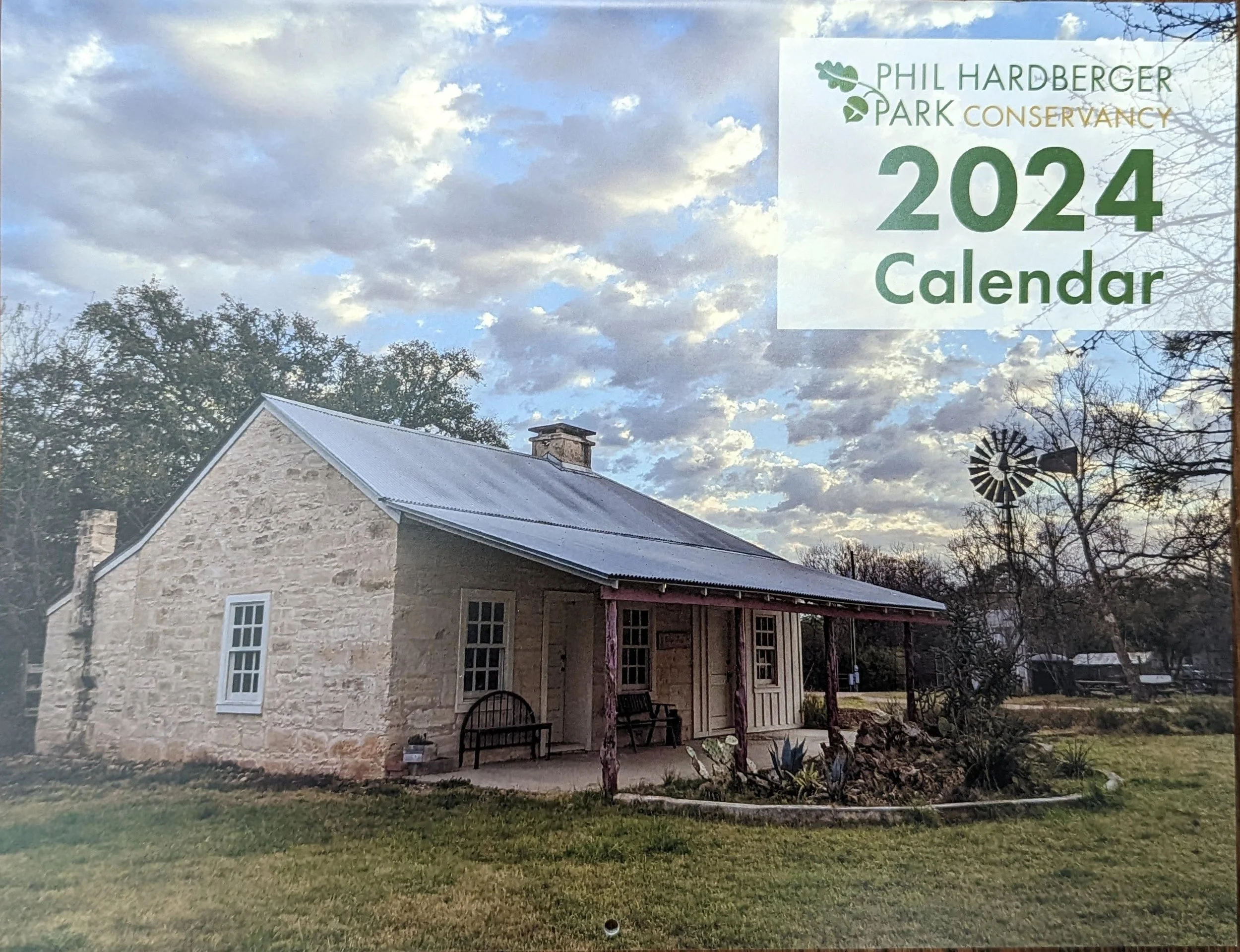

None more so than Stephen Stimson Associates and D.I.R.T. Studio, into whose hands Phil Hardberger Park has been entrusted. Their creative ambition was framed in their vision statement: Phil Hardberger Park will be "a cultivated wild at the edge of San Antonio." Imagining a landscape integrating natural forces and human stewardship, they proposed to regenerate indigenous grasses, reinvigorate oak woodlands and restore riparian flows, while paying homage to Max and Minnie Voelcker and their dairy operations by rehabbing farm structures into an education center.

Yet by itself, Phil Hardberger Park will not reverse San Antonio's shabby legacy of too-few playgrounds or soccer fields, hike-and-bike trails, forests or meadows; we didn't have enough in 1950 for a city of 408,000 and don't today at three times that.

But its creation might mark a watershed moment in local history, sparking a more proactive pursuit of recreational opportunities in a community that only a century ago touted itself as the City of Parks.

That wasn't the most accurate nickname, because it implied a resolute devotion to parklands development that the citizenry knew wasn't true; they had inherited most of the available open space.

Innovative 18th-century Spanish urban planners gave us a street grid centered on Main and Military plazas and demarcated San Pedro Park. In 1899, George Brackenridge built on this tradition when he donated the first 199 acres of what is now the 340-acre Brackenridge Park. A third wave of donations were spinoffs from real estate schemes, including Woodlawn Lake, Collins Park and a clutter of smaller, odd lots that developers have sold to or dumped on the city.

Park development boomed in the 1920s, leading to the purchase of nearly 1,100 acres, a figure not matched for another four decades. Not until the 1960s did San Antonio invest significantly in parks to enhance quality of life, yet even the acres it then purchased to create McAllister Park seemed trivial compared to San Antonio's explosive growth and outward sprawl.

We've been playing catch-up ever since. Despite Proposition 3 and the aquifer-protection zones it has established and City South's designated parklands, we have not yet dedicated ourselves to a well-funded campaign to build and endow a dense network of parks equitably distributed across the city.

Doing so would allow us to preserve farm, forest or ranch lands, and the water courses that flow through them; punch holes in the concrete so that the land and we might breathe; and let us revel in the peace, beauty and pleasure these new parks would provide.

Should Phil Hardberger Park generate such a sustained commitment to a greener and more playful future we just might distinguish ourselves, in Hardberger's words, as "one of the great livable cities of North America."