City Council approves master plan and funds for first phase of design. Phil Hardberger Park already looks like the land suburban development forgot. Now it should remain that way a wooded oasis bisected by busy streets and surrounded by neighborhoods.

The City Council on Thursday approved a master plan for the 311-acre area, along with $852,907 for the first phase of the park's design.

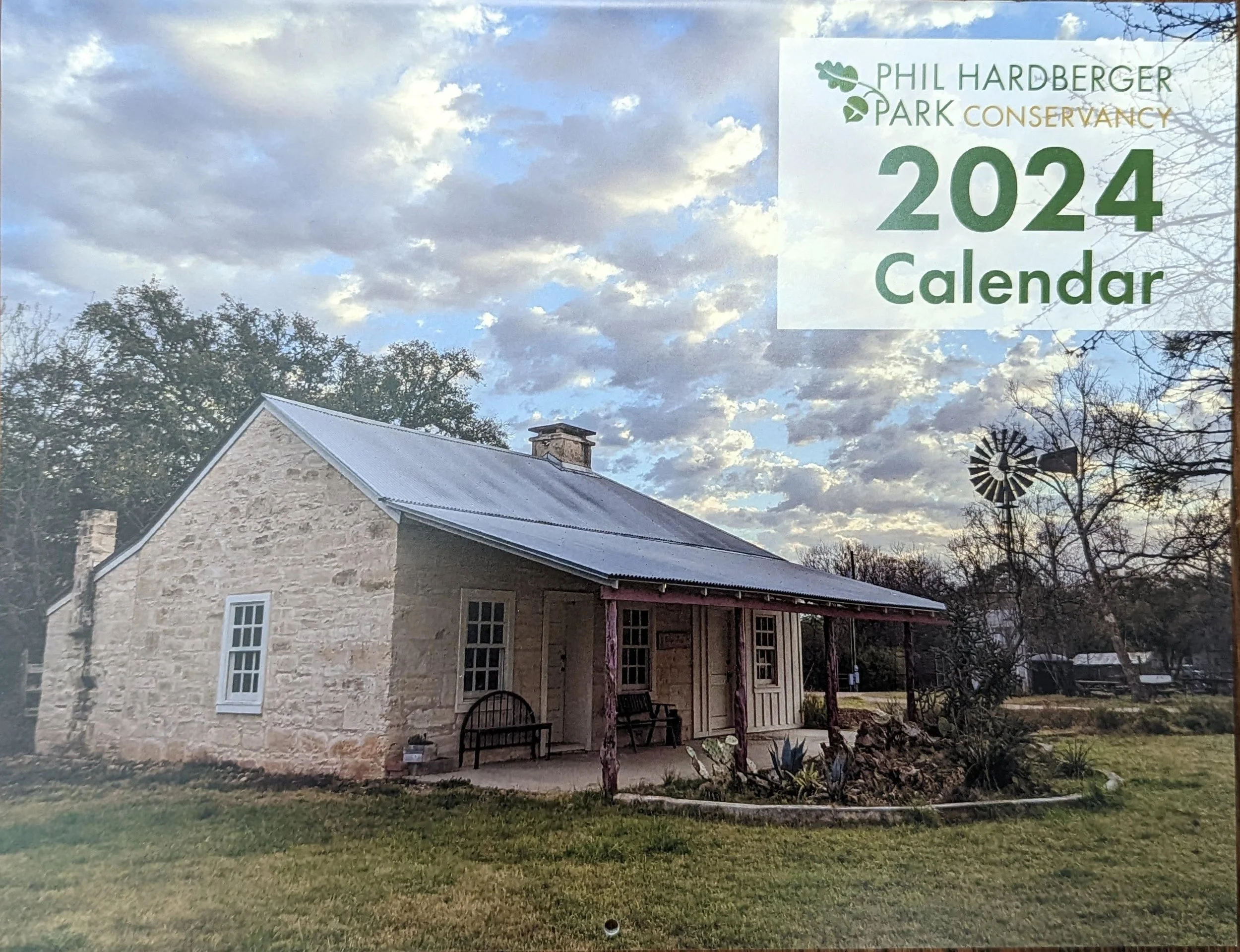

The former dairy farm of Max and Minnie Voelcker is considered the most valuable land in San Antonio that is not going to developers. And in many ways, the design responds to San Antonio's recent suburban sprawl and 10 of tree canopy.

"It's counter to what we've long expected from the North Side," said Char Miller, urban studies professor at Trinity University. "It allows us to maintain a breathing space for the land itself but also for us."

Phil Hardberger Park is the first San Antonio park with a master plan. It’s also believed to be one of the few new large urban parks in America carved out of the center of a city instead of its fringe.

“It’s a precious parcel up there amongst all the development," said Julie Bargmann of D.I.R.T. Studio, one of the firms that designed the master plan.

With an emphasis on urban ecology and habitat restoration, Phil Hardberger Park will be different than others in San Antonio's park inventory.

Although there should be plenty of areas for picnicking and pickup ball games. The idea is to create a place to learn about how nature and urban residents can coexist.

"The whole challenge in urban life today is how we can live with nature without utterly destroying it. Striking that balance is very important for San Antonio," Mayor Phil Hardberger said. ''A lot of our land has been overgrazed and overused. In an urban environment, it's just been scraped off. The goal here is (to achieve) an ecological balance.

The master plan's broad brush concept would give 25 percent of the land to learning centers and pockets of playgrounds, picnic areas and playing fields. A portion of the Voelcker homestead might be transformed into an area where kids could see a few cows and learn about how an early 1900s dairy farm operated.

And the park would introduce San Antonio to something the landscape architects call a "parking grove." Think of it as a parking lot with an abundance of shade tree and a surface that allows water to permeate. Bus stops would play a key role in the plan to get people to the park without driving.

But 75 percent of the property would go to landscape preservation and restoration of Texas brushland, cedar elm woodland, oak woodland, meadow and an oak savanna.

The oak savanna, in particular, would represent the restoration of a habitat once prevalent but now rare in Texas. The savanna – a mixture of prairie and scattered trees – once supported herds of bison. Later, it provided settlers with rangeland.

Today, just 1 percent of an estimated 20 million acres of Texas tallgrass prairie remains, said Bargmann, and bird and wildlife species that threatened and declining. Planting native grasses could provide a habitat for them.

The red-tailed hawk, bob-white quail, lark sparrow, field sparrow, lark bunting, Mexican eagle and Eastern screech owl are a handful of the bird species that might benefit, according to a wildlife survey.

Several loop trails would let visitors meander through the various habitats on bike or by foot, while some ruler-straight paths would move people between loops or across the park in the fastest way possible.

San Antonio's mission history would be reflected in a plan to use acequias – irrigation canals used around the missions – to capture, filter and reuse rainfall and the runoff water to create water features to support animals and plants.

A 175-foot-wide land bridge would allow animals and people to safely cross Wurzbach Parkway. For now it’s a fantasy design feature with no funding, but if the money could be scraped together, it would be a first in the U.S.

"Technically it is possible," said Stephen Stimson of Stimson Associates. Other options for crossing Wurzbach are pedestrian bridges and redesigned drainage culverts.

At least one trail could be open by the end of the year. But Phil Hardberger Park is not yet the "cultivated wild" that the master plan by Stimson Associates would take one to five years.

Among the challenges: oak wilt, illegal dumping in the park, light pollution, invasive plant species, fire ants (which threaten ground-nesting birds, tortoises and small mammals) and the geographic isolation of the park which strains the wildlife population.

Still, the park sits at the intersection of the Edwards Plateau Savanna, the Blackland Praire and the South Texas Plains, a location that gives the land the ability to (missing copy)

Were it not purchased by the City, there's little doubt that the three eco-regions would have become a series of upscale gated neighborhoods.

"The North Side has definitely suffered from knocking all the trees down. That path is continuing," Hardberger said.

"We're running out of beauty and things that feed our soul. A city that's getting bigger and uglier describes a lot of American cities. That's not the goal.”